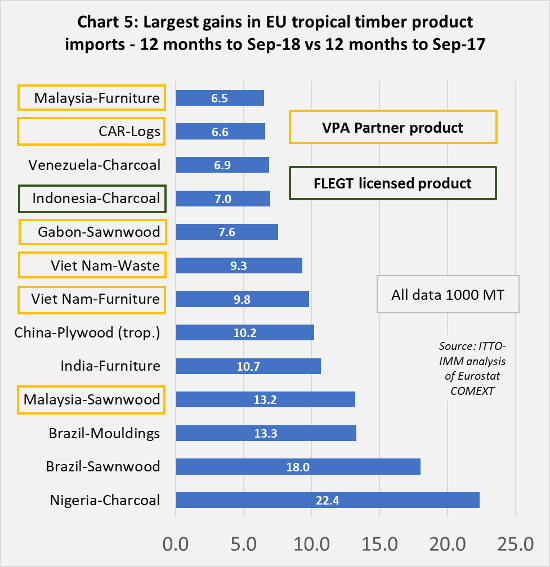

After a dip in 2017, EU imports of tropical wood products have recovered ground in 2018. Most of the gains this year have been in imports from countries not engaged in the VPA process, including Nigeria, Brazil, India and China.

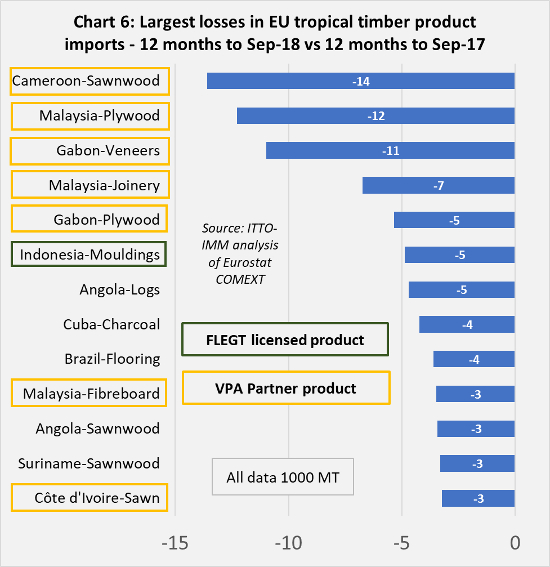

A significant proportion of the gain has been in charcoal from Nigeria and Venezuela which lie outside the scope of the EU Timber Regulation. These gains have offset a decline in imports of several commodities from a variety of countries including sawnwood from Cameroon, joinery and plywood from Malaysia, veneers and plywood from Gabon, and mouldings from Indonesia.

(Click here to view the full series of charts accompanying this article with descriptive notes).

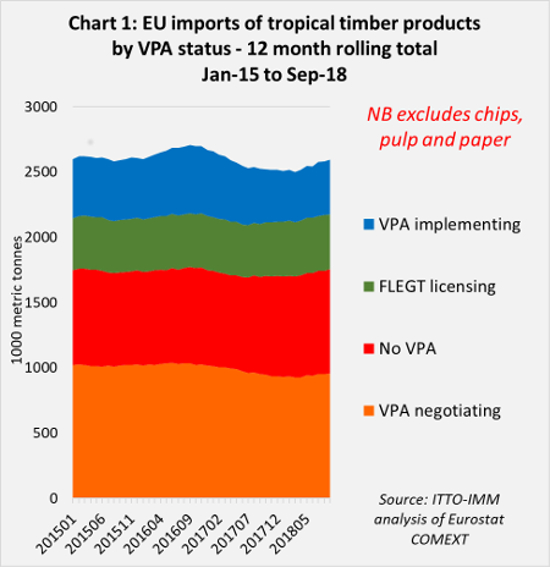

The EU imported 2.60 million metric tonnes (MT) of tropical timber products (excluding chips, pulp and paper) in the year ending September 2018, up from 2.53 million MT in the previous 12-month period. Over the same timespan the euro value of EU tropical timber imports declined from €3.78 billion to €3.75 billion. However, as the euro strengthened against the dollar during this period, the dollar value of EU tropical timber imports increased from $4.17 billion to $4.41 billion.

The EU imported 2.60 million metric tonnes (MT) of tropical timber products (excluding chips, pulp and paper) in the year ending September 2018, up from 2.53 million MT in the previous 12-month period. Over the same timespan the euro value of EU tropical timber imports declined from €3.78 billion to €3.75 billion. However, as the euro strengthened against the dollar during this period, the dollar value of EU tropical timber imports increased from $4.17 billion to $4.41 billion.

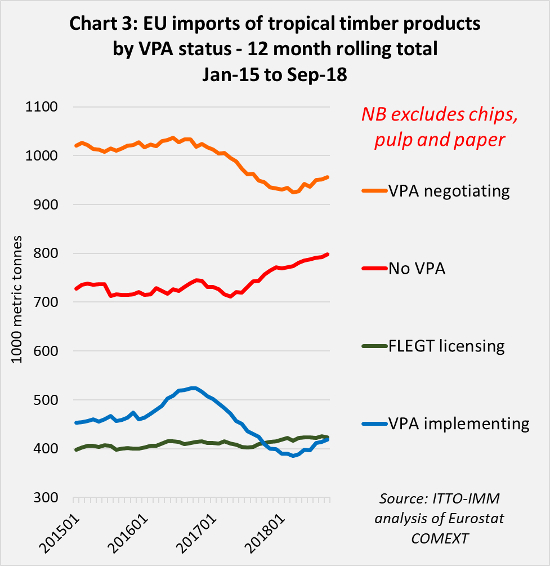

EU imports from Indonesia, currently the only FLEGT licensing country, have increased slowly during 2018. EU imports from Indonesia were 420,000 MT in the year ending September 2018 compared to 410,000 MT in the year ending September 2017. Most of the gains were in plywood and charcoal. EU imports of wood furniture, joinery and sawn/decking products from Indonesia have been flat this year, while imports of flooring have continued to decline.

Volatile EU imports from VPA implementing countries in Africa

EU imports from the five VPA implementing countries in Africa (Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo Republic, Ghana, and Liberia) have been very volatile in recent years. 12-month rolling imports increased sharply to 525,000 MT in October 2016 and then fell even more rapidly to a low of 385,000 MT in February 2018. Since then, imports have recovered some lost ground to reach 418,000 MT in the year ending September 2018.

A range of factors have contributed to the volatility in EU imports from Africa in recent times including logistical problems and delays with shipping out of Douala port in Cameroon, overstocking in the EU in 2017 following arrival all at once of a large volume of delayed shipments from Africa, diminishing commercial availability of tropical hardwood species of interest to European buyers, delayed payment of VAT refunds by African governments which created financial challenges for operators in the region, and increasingly rigorous EUTR enforcement which, in the absence of FLEGT licenses, has placed a greater onus on EU importers to demonstrate the legal origin of timber.

Much of the recent volatility in EU trade in timber from African VPA implementing countries is attributable to sawnwood imports from Cameroon, particularly in Belgium. This year, continuing weakness in EU trade with Cameroon has been partly offset by recovery in imports of logs from the Central African Republic and logs and sawnwood from Congo.

EU imports from Ghana, mostly of sawnwood, have been low and flat this year, with the 12-month rolling total stable at 25,000 MT, less than half the quantity of two years ago. EU imports from Liberia remain low but have picked up since the start of 2018, with the 12-month rolling total rising from 3,000 MT in January 2018 to 6,000 MT in September 2018.

EU imports from Ghana, mostly of sawnwood, have been low and flat this year, with the 12-month rolling total stable at 25,000 MT, less than half the quantity of two years ago. EU imports from Liberia remain low but have picked up since the start of 2018, with the 12-month rolling total rising from 3,000 MT in January 2018 to 6,000 MT in September 2018.

EU timber imports from the VPA negotiating countries have also been volatile in recent years, the 12-month rolling total falling continuously from over 1 million MT in September 2016 to a low of 930,000 MT in April 2018 and bouncing back to 960,000 MT in September 2018. However, these overall figures hide significant variations between VPA negotiating countries, which are a very diverse group.

Of VPA negotiating countries, Malaysia is the largest supplier to the EU in tonnage terms, accounting for around a third of the total. This year EU imports of sawnwood from Malaysia have strengthened, particularly due to good demand in the Netherlands, although this gain has been offset by a decline in EU imports of Malaysian plywood, laminated window scantlings, and fibreboard.

EU imports from Vietnam strengthen this year, after a dip in 2017

Vietnam is the second largest supplier amongst those countries categorised here as a “negotiating country” (Vietnam, together with Honduras and Guyana, recently completed VPA negotiations and will be identified as VPA “implementing countries” in future reports). EU imports from Vietnam consist almost entirely of wood furniture, with trade in this commodity strengthening this year after a dip in 2017. 12-month rolling total furniture imports into the EU from Vietnam increased from 220,000 MT at the end of 2017 to 230,000 MT in September 2018.

Another potentially significant trend is that Denmark started to import larger volumes (up to 2,500 MT per month) of waste wood (for biomass energy) from Vietnam this year.

Of the three VPA negotiating countries in Africa, Gabon is the largest supplier to the EU. After declining from 220,000 MT in 2016 to 183,000 MT in 2017, EU imports from Gabon remained flat at the lower level in 2018. EU imports of veneer and plywood from Gabon have fallen sharply this year, only partly offset by a recovery in imports of sawnwood from the country. EU imports from DRC (mainly logs and sawnwood) and Côte d’Ivoire (mainly sawnwood and veneer) declined in 2017 and have remained at the lower level in 2018.

Of the three VPA negotiating countries in Africa, Gabon is the largest supplier to the EU. After declining from 220,000 MT in 2016 to 183,000 MT in 2017, EU imports from Gabon remained flat at the lower level in 2018. EU imports of veneer and plywood from Gabon have fallen sharply this year, only partly offset by a recovery in imports of sawnwood from the country. EU imports from DRC (mainly logs and sawnwood) and Côte d’Ivoire (mainly sawnwood and veneer) declined in 2017 and have remained at the lower level in 2018.

The two countries in Latin America that recently completed VPA negotiations, Guyana and Honduras, are both currently only small suppliers of timber to the EU. 12-month rolling total imports into the EU from Honduras were flat and running at around 2,000 MT throughout 2017 and the first nine months of 2018, about half the level of 2015. Most comprised sawn softwood. EU imports from Guyana, mainly consisting of hardwood logs and sawn, fell sharply from 8,000 MT in 2015 to only 3,000 MT in 2016, but since then have recovered some ground and were 4,000 MT in the year to September 2018.

Policy implications of rising imports from non-VPA countries

Meanwhile EU imports of tropical timber products from countries not engaged in the VPA process increased from 740,000 MT in the year to September 2017 to 800,000 MT in the year to September 2018. This is primarily due to continued increase in imports of hardwood sawnwood and decking from Brazil, charcoal from Nigeria and Venezuela, tropical hardwood plywood from China, and furniture from India.

Rising EU imports from countries not engaged in the VPA process have potentially significant policy implications. In the case of charcoal from Nigeria and Venezuela, the rising trade relates to a product not currently covered by EUTR or within the scope of the VPAs. However, charcoal from these two countries competes directly with the same product from Indonesia. From both a forest conservation and competitiveness perspective, it may make sense to extend both EUTR and FLEGT licensing to include charcoal.

The other non-VPA products are also all significant competitors to FLEGT licensed timber from Indonesia. The rise in EU trade in these products, during a period when imports from Indonesia have remained flat, implies that licences are not, at present, overriding other factors determining relative competitiveness (such as logistics, exchange rates, manufacturing costs etc). It also indicates that EU operates can obtain adequate assurances of legality to meet their EUTR obligations from suppliers in these countries even in the absence of licenses. Either that or EUTR regulators are not being enforced with the rigour required to identify potential illegality risks in these product supply chains.

The other non-VPA products are also all significant competitors to FLEGT licensed timber from Indonesia. The rise in EU trade in these products, during a period when imports from Indonesia have remained flat, implies that licences are not, at present, overriding other factors determining relative competitiveness (such as logistics, exchange rates, manufacturing costs etc). It also indicates that EU operates can obtain adequate assurances of legality to meet their EUTR obligations from suppliers in these countries even in the absence of licenses. Either that or EUTR regulators are not being enforced with the rigour required to identify potential illegality risks in these product supply chains.

An assurance that implementation of EUTR is increasingly effective comes from the latest EC biennial report (see next report). Further reassurance that a failure in EUTR implementation is not the main reason for the continuing rise in EU imports of wood products from non-VPA countries is the fact that a large proportion of these products are destined for EU countries that have been particularly active in EUTR enforcement, including the UK, Netherlands and Germany.

Nevertheless, this analysis highlights that in the interests of ensuring a level playing field and to maximise the market benefits of FLEGT licensing, efforts to ensure uniform and effective application of EUTR should continue to be prioritised. Furthermore, EUTR regulators should be encouraged to focus attention on the rigour of due diligence procedures with respect to these various products from countries not actively engaged in the VPA process.