Vietnamese VPA expected to create positive regional dynamics

IMM spoke with Edwin Shanks, VPA Joint Implementation Coordinator for Vietnam, about latest developments in the country. Vietnam is regarded as a processing hub in the timber sector in Southeast Asia and is an important supplier, in particular of indoor and outdoor furniture, for the EU market. In 2015, Vietnam exported timber and timber products to 106 countries worldwide with a total export value of around $6.8. The country imports roughly 40% of its wood requirements,

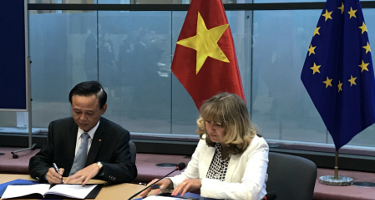

including roundwood supplies from 60 countries and sawn timber from 80-90 countries. Its main suppliers in recent years have included Laos, USA, Cameroon, Cambodia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Chile amongst others. Vietnam also imports timber supplies from several EU countries such as Germany, Belgium and Finland. Domestic timber processed in Vietnam mainly comes from plantation forests. VPA negotiations between the EU and Vietnam took place between 2010 and May 2017; and the Agreement is now in the process of being ratified by both sides. At the same time, preparatory work for implementation of the VPA is already in full swing.

IMM: Edwin, you are the Joint Implementation Coordinator for Vietnam – what exactly does this mean?

Edwin Shanks (ES): As Joint Implementation Coordinator I work with all groups of stakeholders – from the Vietnamese government and the EU Delegation in Hanoi to DG Environment in Brussels as well as the private sector and civil society stakeholders. My position is to be neutral and provide information, facilitate dialogue and coordinate actions and activities between these different groups of stakeholders in the implementation process. My main role is to support both Vietnam and the EU in implementing the mechanisms of the VPA. I also look for opportunities to create stakeholder engagement in the process, for example through consultations and FLEGT projects.

IMM: Vietnam is currently preparing for VPA implementation. What kind of work does this involve?

ES: The agreement was initialled in May 2017, when negotiations were concluded. The EU and Vietnam are now going through their separate ratification process. I’m expecting these will be completed sometime in the second half of next year and the Agreement will then be formally ratified and will become legally binding. At the same time, the two parties are already putting the necessary mechanisms in place for managing VPA implementation. This includes convening a Joint Preparation Committee made up of senior representatives from the EU Delegation in Hanoi and the Vietnamese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. This Committee will later be renamed Joint Implementation Committee and its role will be to guide and monitor the implementation process. Vietnam is also in the process of preparing a Joint Implementation Framework, which will define actions that need to be taken and how different stakeholders will be involved. Another important point is capacity building and the development of new legislation and systems. The Timber Legality Definition as well as the Vietnam Timber Legality Assurance System (VNTLAS), which form an essential part of the VPA, are primarily based on existing laws and regulations. At the same time, Vietnam also made some commitments to develop new legislation, for example relating to timber import controls, a risk-based classification of enterprises, the process of verification for timber exports, and the FLEGT Licensing Scheme that will cover exports to the EU. Preparatory work for these elements is already underway.

IMM: What are the main challenges you are currently foreseeing for VPA implementation in Vietnam?

ES: I think I would identify two particular challenges. The first is the large scale and diversity of the timber industry in Vietnam. Just to give an indication of that, there are over 4500 formally registered timber processing and trading enterprises – both Vietnamese and foreign-direct investment companies. Added to this are several hundred wood industry processing villages, that is clusters of small enterprises that concentrate on timber processing, and many thousands of small-scale timber processors like small sawmillers, artisans etc., especially in rural areas. And then Vietnam has millions of timber-growing households that provide domestic timber supply. So it is a very diverse sector with many different private sector players and communicating to all these actors about the VPA and VNTLAS and bringing them all into the process of implementing the system will be rather challenging. A second major challenge is relating to broader communications about the VPA, for example to ensure that markets in different regions of the world are informed of the progress that is being made and to effectively mobilise market awareness and support. It will be important to transmit a more balanced picture than the one some actors, like some environmental organisations or risk rating organisations, are currently painting of Vietnam. The challenge of tackling illegal timber imports and cross-border trade, for example, is a key part of the VPA. The VPA provides for a strengthening of import controls through a number of filters like species risk, geographic origin risk and customs risk. At the same time, a new obligation to carry out due diligence for timber imports will be introduced. Many Vietnamese processors are already shifting their supply patterns to make use of certified timber imports, for example in response to the EU timber regulations and the requirements of other markets. This is not to say the problem of utilization of illegal timber by Vietnam’s timber processors is not important, but it will take some time to fully introduce and implement these measures. In the meantime, effective communication with markets and consumers will be needed to show the steps, which are being taken.

IMM: Vietnam is an important importer of wood from the Mekong region. What does a Vietnam VPA mean for the region?

ES: The timber industry in Vietnam utilises both domestic and imported timber; as I mentioned approximate figures suggest that around 40% of the timber used is imported and 60% comes from domestic sources. There are different sets of issues with these different sources of timber. Where domestic timber is concerned, because these supplies come mainly from small-scale plantations for which farmers have land use rights, the timber is basically legal, but a major challenge is obtaining all the necessary paperwork and evidence from hundreds and thousands of small suppliers.

Where imported timber is concerned we are expecting the Vietnam VPA, once it is fully up and running with its timber import controls and due diligence requirements, to have a positive impact in the region.

Recent experience has shown that when countries in the region put in place more stringent controls of timber exports this can influence trade flows quite substantially. We can hope that when both supplier and importing countries in the region take parallel actions then the net effect on illegal timber trade will be substantial.

IMM: Will Vietnam require proof of legality for all timber imports under the VPA?

ES: Yes, importers will have to carry out due diligence for all imported timber. And then depending on the risk category of the imported timber consignment, additional documentary evidence and proof of legality in the country of harvest will be required.

IMM: Will the Timber Legality Assurance System cover all exports from Vietnam or just those to the EU?

ES: The VNTLAS will cover all export and domestic markets. The FLEGT-licensing scheme will only apply to exports to the EU but all other procedures, including the procedures for verification of timber exports will apply to all markets. The Government of Vietnam will introduce an organisations classification system, which is a risk-based assessment of timber production, processing and trading enterprises. All companies will need to register with this system and their level of compliance will be appraised according to requirements in the timber legality definition. Companies will then be classified as either “compliant” or “non-compliant” and the level of verification of exports and checks on enterprises and shipments going into export will vary according to this classification: non-compliant companies will be subject to much stricter physical and documentary checks.

IMM: Will private certification schemes play a role in the Vietnamese VPA?

ES: Yes, that’s quite an interesting part of it. The VNTLAS will recognise voluntary or private certification schemes and possibly national certification schemes, particularly with respect to timber imports – certification can be used as additional documentary evidence of legality. This has been agreed in principle and broad criteria for how certification can be used and which schemes will be recognised are being developed.

Another interesting point is that Vietnam will also recognise timber imports that come with a FLEGT license from other VPA countries with a fully operational FLEGT-licensing scheme. Such timber will be considered as automatically legal. This might again create some positive cross-country or regional dynamics in the Mekong region in the next few years – or be an incentive for African VPA partner countries to complete implementation of the agreement, for example.

IMM: How will the Vietnamese VPA contribute to improving governance and tackle corruption in the country?

ES: Corruption is obviously a concern, which is expressed by different stakeholders. I think there are a number of ways in which the VPA can strengthen forest governance. Firstly, the VNTLAS and the timber legality definition are based on the existing legal framework as well as new legislation to be put in place, and these are being put more and more in a structured system, for example where timber supply chain controls or verification of timber exports are concerned. This systematisation of the legislative and regulatory framework will create a more coherent and predictable system.

A second aspect will be the strengthening of law enforcement and the strengthening of management of law enforcement, which is part of the agreement.

Moreover, the VPA provides for public disclosure of information. This creates an important baseline for making information available to the private sector and civil society and increases transparency.

And the VPA includes independent evaluation or audit function of both the Agreement and the VNTLAS as well as independent monitoring conducted by civil society organisations. So through these various channels I think it can be expected the VPA will have a positive impact on governance. On the other hand, there are also some potential negative implications that need to be considered, such as increased transaction costs and administrative burden for enterprises and government verification agencies to handle the procedures.

IMM: This sounds like quite a lot of work ahead of you and the Vietnamese partners – how long do you expect the implementation process to take?

ES: Implementing the VPA in Vietnam will be complicated due to the aforementioned diversity of the sector. I expect that the Agreement will be ratified and legally enter into force in the second half of 2018. In parallel and beyond that there will be the development of legislation and management information systems, capacity building etc., which will take a number of years. This process leads up to a joint assessment of the readiness of the VNTLAS: When all the elements of the VPA and the VNTLAS are in place, the two parties – Vietnam and the EU – will conduct this independent assessment to determine whether the system is ready. This assessment may also be done in stages and subsequent to the successful outcome the FLEGT licensing scheme will commence. Like I said this part will take several years – I’d say we are currently looking at the beginning of the next decade, maybe 2021 or 2022 for full implementation. A robust system takes time to develop and implement. We have to bear in mind that VPA implementation is a far-reaching process that aims to develop a national system that is applied to all markets as well as involving all actors

Any questions or comments on VPA implementation in Vietnam can be directed to Mr Shanks at e.shanks@mandala.vn. Within the Vietnam Administration of Forestry Ms Nguyen Tuong Van, Deputy Director Department of Science & Technology and International Cooperation (DOSTIC) as well as Chief of the Standing Office for VPA/FLEGT Viet Nam, can be contacted for further information under van.fssp@gmail.com