As at previous IMM trade consultations in France, Germany and the UK, the main section of the Antwerp event opened with a workshop on trends in EU tropical timber trade. The workshop’s primary purpose was to discuss drivers of market decline and future opportunities for tropical timber in Europe with private sector representatives.

A short presentation by IMM Trade Analyst, Rupert Oliver, set the stage by summarising recent trends in global tropical timber trade and the EU’s changed position in the global trade environment. This highlighted that the share of tropical timber in total EU imports was only 19.7% in 2018, down from 20.3% in 2017 and the third consecutive year of decline (after a brief rebound in 2015). Longer term, the share of tropical countries in EU imports have fallen from well over 30% before the financial crises in 2007-2008.

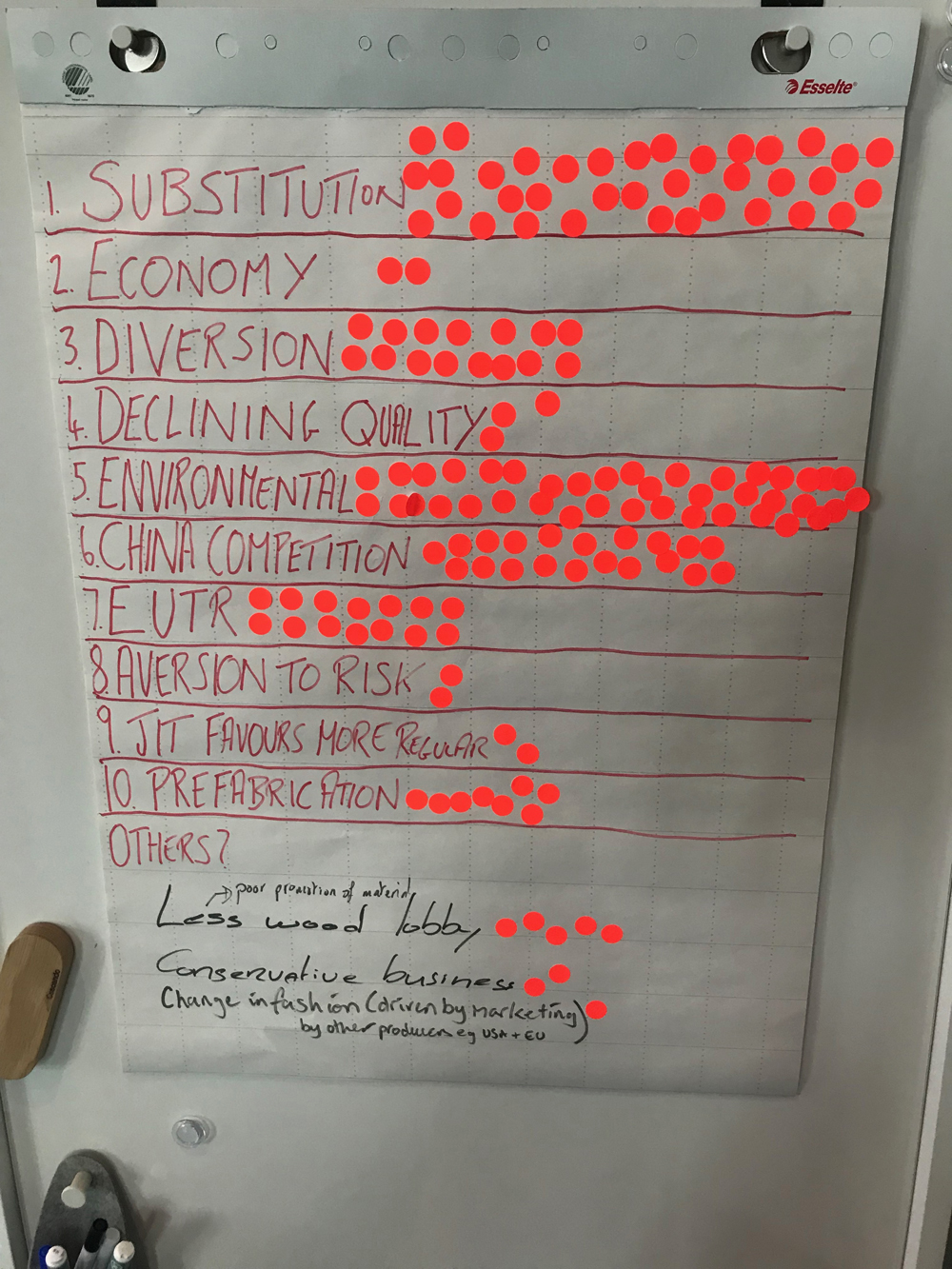

Drawing on data from the 2018 survey and previous trade consultations, IMM had identified 10 potential drivers of tropical timber’s decline in the European markets (see Table 1). As at the earlier consultations, participants at the Antwerp event were invited to identify any additional drivers, and to rate their relative significance (Image 1). Participants identified two additional drivers, “conservative European business” and “changes in fashion”, although neither was considered more significant than those previously identified by IMM.

Unlike the 2018 survey and earlier consultations (when “product substitution” was rated most highly), Antwerp participants rated “environmental prejudices and uncoordinated marketing” as the most significant driver of tropical wood’s decline in the European market. “Product substitution” was in second place. The related factors of “competition from China” and “diversion of wood supply to other markets” were viewed as the next most significant, in line with previous IMM research.

It’s notable that all four of these factors were rated more significant drivers of tropical wood’s market decline in Europe than “the challenge of obtaining assurances of non-negligible risk for EUTR”. This reinforces the message of previous IMM research, that the “green lane” for FLEGT licensed timber in EUTR, while offering some immediate market benefits, will not be sufficient in isolation to override other more significant drivers of tropical timber’s market decline in the EU.

In contrast to previous IMM research, participants in Antwerp rated the “economic downturn and slow economic recovery” as a much less significant factor. This may simply be a sign that as time passes, memories of the economic downturn are gradually receding and there is growing acceptance that slow economic growth is the “new normal”. And in the Netherlands, where economic growth has been reasonably robust in the last 2 years, it’s unlikely now to be viewed as such a significant market factor.

|

Drivers of tropical timber’s decline in Europe |

Antwerp votes |

Antwerp rank |

IMM 2018 survey rank |

|

Environmental prejudices and uncoordinated marketing |

41 |

1 |

4 |

|

Substitution by temperate, chemically and thermally modified wood, composites and non-wood materials |

32 |

2 |

1 |

|

Competition from China for wood supply & in markets for finished goods |

17 |

3 |

5 |

|

Diversion of tropical wood supply to other markets |

14 |

4 |

3 |

|

Challenge of obtaining assurances of non-negligible risk for EUTR |

9 |

5 |

na |

|

Prefabrication – switch from adaptable utility woods to tightly specified material |

7 |

6 |

8 |

|

Declining wood quality linked to pressure on tropical forest resource |

3 |

7 |

na |

|

Economic downturn 2008-2013 followed by slow economic recovery 2013-2018 |

2 |

8= |

2 |

|

Import and financial sectors aversion to commercial risk |

2 |

8= |

6 |

|

Just-in-time favours more regular & less volatile supply |

2 |

8= |

7 |

|

Conservative European business |

2 |

8= |

na |

|

Change in fashion – driven by European and North American suppliers and manufacturers |

1 |

12 |

na |

Having rated the factors driving tropical wood’s market decline in the EU, participants were divided into smaller groups and asked to discuss and provide feedback on three questions: (1) can the market for tropical timber products in Belgium/Netherlands and wider EU be turned around; (2) if so, how; and (3) what role do you think the FLEGT process can play in turning the market around?

On the first question, quite a few participants felt there was little or no prospect of the market turning around, suggesting that share has now been irretrievably lost to other materials and demand for tropical wood has shifted elsewhere in the world. However others responded with a cautious “yes, in some specific market sectors”.

On the second question, of “how to turn the market around”, it was noted that trying to encourage more demand by focusing on traditional product groups and business-to-business communication channels, and trade servicing activities, was unlikely to lead to any significant increase.

On the other hand, there was some optimism that new opportunities could arise through the introduction of better organised and targeted marketing campaigns, involving considered analysis to match specific tropical timbers and products to niche markets, and backed by widespread certification and/or licensing, and concerted efforts to explain the narrative behind legal and sustainable tropical timber products to customers.

Delegates ranked factors impacting tropical timber sales

Mixed views on FLEGT market impact

Views were divided on the third question, just how important FLEGT licensing is likely to be as part of the process? Some participants seemed sceptical that licensing had an important role to play, others were more enthusiastic. To some extent this split reflected the experience to date with marketing of Indonesian FLEGT products. There was a widespread view in the room that companies so far have not been switching to Indonesian products due to the availability of FLEGT licenses.

However it was also acknowledged that the market situation varied widely by product group and the lack of a more positive response was linked to the fact that only a limited range of companies in the room were interested in the products perceived to be most readily available from Indonesia (bangkirai decking, higher-end tropical hardwood plywood, and exterior furniture).

In short, licensing was helping those companies that have traditionally purchased from Indonesia but had yet to encourage any broader interest in Indonesian products in the European market. Longer term, FLEGT licensing was expected by some participants to play a larger role if the range of countries and products covered by licensing increased. The forest sector reforms and new procedures implemented during the FLEGT VPA process were seen as part of a positive narrative that could help at least to maintain, if not necessarily grow, market share in the EU, but there are broader issues of tropical wood market development that also need to be addressed.

There was also stronger support for the regulatory approach adopted by the EU, combining FLEGT licensing with EUTR, when participants were asked, as a final exercise, to rank overall strategies that might be adopted to improve the position of tropical wood products in the European market (see Table 2).

Of the various strategies identified in previous survey work by IMM, the FLEGT regulatory approach was by far the most popular amongst Antwerp participants. No single participant reckoned that the opposite strategy, of repealing the FLEGT licensing measures and EUTR (and thereby in theory reducing the regulatory burden associated with importing timber products) would help to improve tropical timber’s position in this market.

|

Strategies to improve the position of tropical timber in the European market |

Antwerp Votes |

Antwerp Rank |

|

A regulatory approach involving increased supply of FLEGT-licensed tropical timber linked to consistent and effective enforcement of EUTR to remove illegal wood |

30 |

1 |

|

A voluntary approach involving increased supply of FSC/PEFC certified tropical timber linked to implementation of “responsible procurement policies“ (e.g. through STTC) & branding of certified tropical wood (e.g. ATIBT Fair and Precious) |

23 |

2 |

|

Liaison with NGOs |

18 |

3 |

|

Recognise FLEGT licensed timber as equivalent to FSC & PEFC in government procurement |

17 |

4 |

|

Gather LCA data on tropical timber & promote wider environmental benefits (e.g. carbon) |

17 |

5 |

|

Focus on promoting technical qualities of tropical timber to engineers, architects and specifiers, including preparation of technical data on commercially available tropical timber species (incl. LKS) |

12 |

6 |

|

Encourage/support greater engagement of tropical wood industry in technical standards-setting bodies in the EU |

10 |

7 |

|

Move up the value chain to produce more secondary, tertiary and engineered products |

4 |

8 |

|

Pro-active steps to build B-to-B relationships between tropical exporters and EU distributors and manufacturers, for example through trade missions, sponsorship for participation at trade shows. |

3 |

9 |

|

Research work to match specific tropical timbers to end-user applications in EU |

2 |

10 |

|

Deregulation. i.e. repeal EUTR & FLEGT VPA obligations for mandatory licensing in partner countries |

0 |

Rejected |

Participants in Antwerp strongly favoured combining the FLEGT regulatory approach with further efforts to expand supply of third-party tropical timber. Perhaps unsurprising in this part of the EU where there has been particularly strong support for timber procurement policies favouring certified timber.

Participants also strongly endorsed a view that NGOs need to be actively engaged in efforts to improve the market position of tropical timber in the EU. Specifically, participants noted that the three NGOs which, probably, have been most influential on forestry issues in the EU (WWF, FoE and Greenpeace) need to be convinced of the “use it or lose it” message and to be more visible in their support for the FLEGT process.

Need to improve tropical timber image

Taken together, the demand for a regulatory approach in combination with wide-ranging commitment to private sector certification, and direct liaison with NGOs, mirrors the high ranking accorded to “environmental prejudices” as a key driver of tropical wood’s decline in this part of the EU. There was a strong feeling in this audience that the poor environmental reputation of tropical timber products, irrespective of just how well deserved, must be rectified by far-reaching corporate commitments to good practice, backed by regulation, as an essential pre-requisite to maintain or rebuild market share.

There was some support for the view that FLEGT licensing should given equal recognition to FSC and PEFC certification in government timber procurement policy amongst participants, but this view was far from universal. This may reflect views expressed later in the day that there is limited understanding of the relationship between the FLEGT process and “sustainable” forestry operations in tropical countries. There was a strong feeling that more work needs to be done to examine, and communicate, the extent to which the FLEGT process is driving sustainable forestry operations rather than merely confirming conformance to existing laws (seen by participants as the minimum requirement and no more than “business as usual”).