A new study of EU Member State public procurement policies and their recognition of FLEGT Licences found that twenty–two EU member states now possess some form of public procurement policy for products containing or made from wood. They vary significantly in terms of their definition of criteria, coverage of products, applicability to different levels of government and whether they are voluntary or mandatory. However, they all require, or at least encourage, government buyers to source legal and often sustainable, timber.

Public procurement policies can play an important role in encouraging trade in legal and sustainable timber. Government purchasing of timber can account for a significant proportion of all timber purchasing in a given country, and therefore has considerable potential to influence buying practices and to promote good business practices across the timber market as a whole.

The full study can be downloaded here.

The importance of public procurement for timber markets

The importance of public procurement to the marketplace makes government procurement policy a key instrument in attaining the vision set out in the Europe 2020 Strategy (the 10-year strategy proposed by the European Commission in 2010 for advancement of the economy of the EU). It aims at “smart, sustainable, inclusive growth”, with greater coordination of national and European policy.

Sustainable procurement is therefore about using public spending to achieve social and environmental objectives, and to strategically use the public sector’s economic power to catalyse innovation in the private sector.

The study found that public policies and the public sector are perceived to play a significant role in the EU market place for forest products, though the exact contribution is hard to define. Many member states have invested heavily in setting policies through complex processes with great consideration paid to policy content. Most EU member states have mandatory purchasing policies for central government departments and voluntary policies for local authorities and other agencies. The majority of public spending is undertaken at a local government level though and little monitoring of policy compliance has been directly observed. Most EU member state governments do not know how much wood they purchase and therefore have no indication of how much sustainable, legal or FLEGT-licensed material might be included within their procurement.

Policy coverage and acceptance of FLEGT-licenses

In total, the analysis indicates that 22 member states have some form of policy. Six currently have no public procurement policy – Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Portugal and Romania. Poland has developed a National Action Plan, but no specific criteria have been identified for wood–based products. Portugal has indicated that it will potentially include all EC GPP product/use categories in future policy. Estonia, Greece, Hungary and Romania remain the only EC member states without a policy or any identified plans to develop such policies.

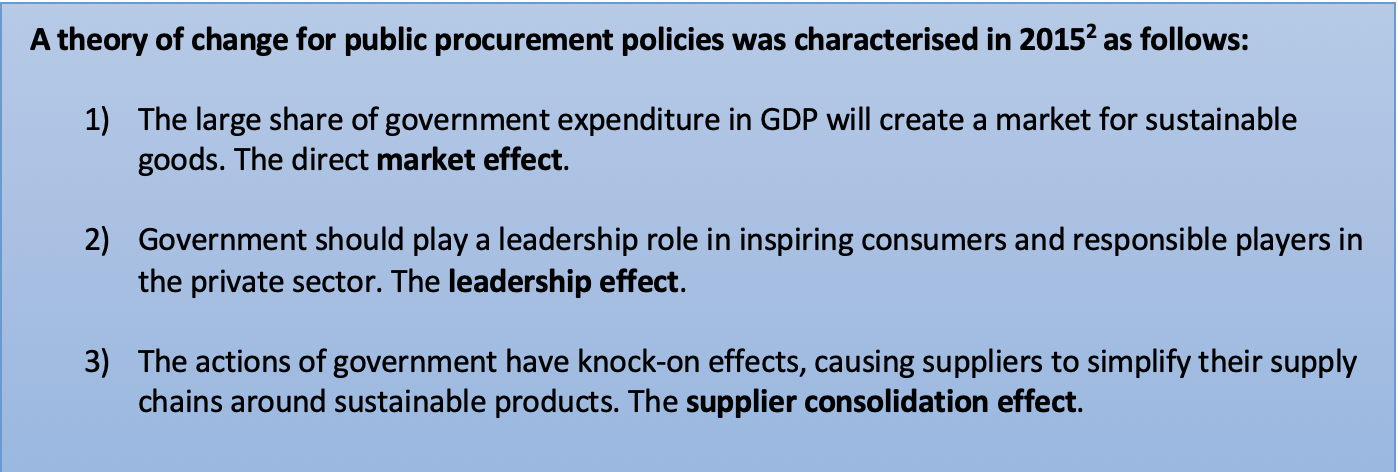

Figure 1 indicates that the range of end–uses and product types covered by the policies scrutinised is variable. Only 13 of the 28 states appear to have what might be termed comprehensive coverage in their procurement policies. Eighteen make reference to office and/or graphic papers and 19 make specific reference to furniture. Fifteen policies make reference to the timber used within “construction”, though this varies, with those countries using the EU GPP criteria only applying the policy for “timber in office building design, construction and management”.

Thirteen countries appear to have comprehensive policies that in theory apply to all purchases of timber products. Of these, Luxemburg’s policies (alone in this case) apply to all products that are within the scope of the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR). Germany and the UK’s policies apply to all products that contain virgin wood fibre.

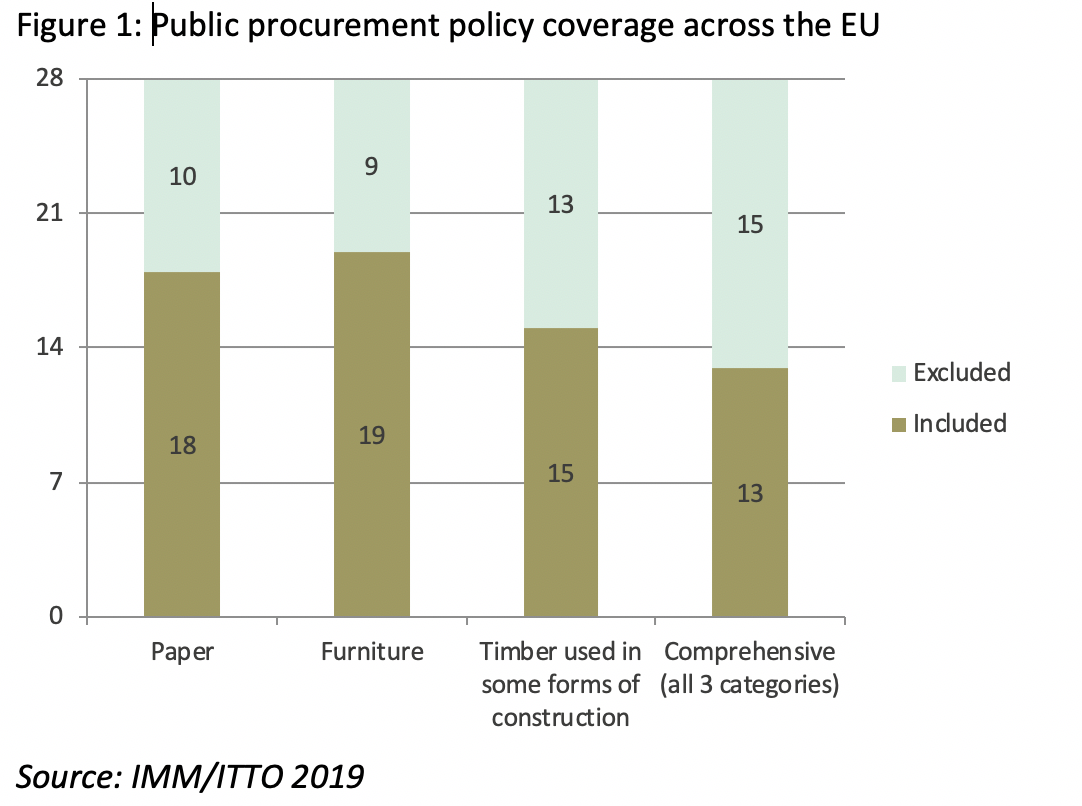

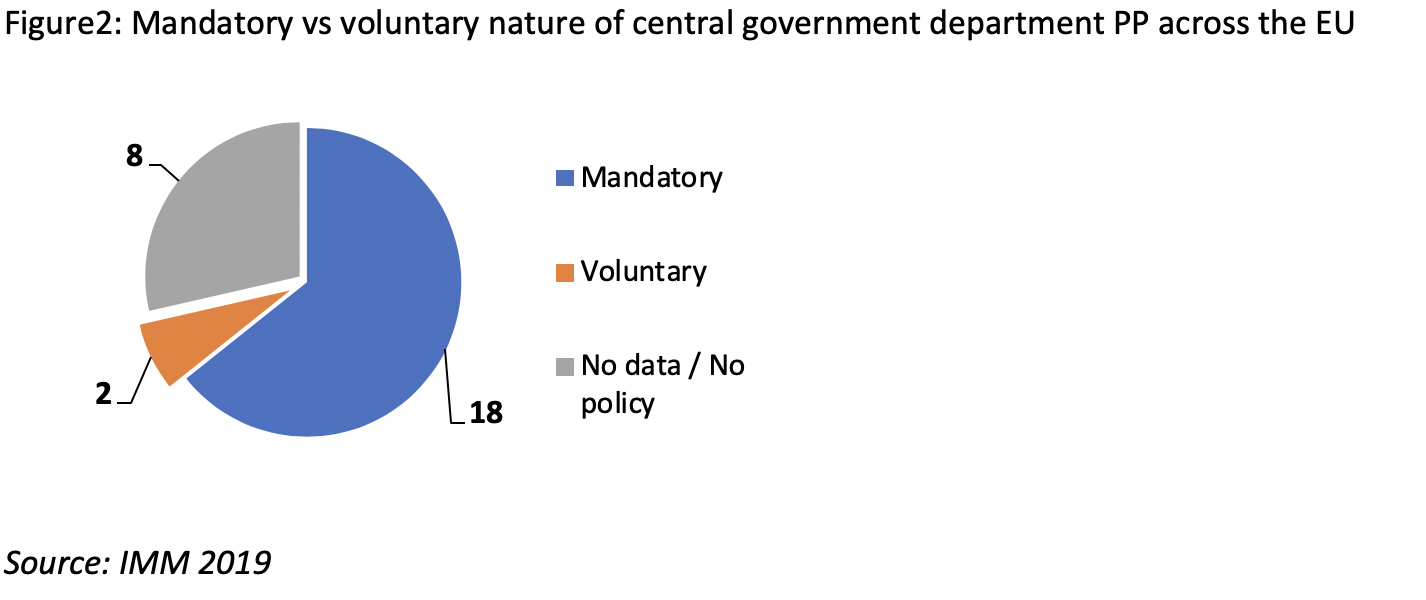

Figures 2 and 3. contrast the balance between mandatory and voluntary applicability for central and local government departments with respect to the policies. At central government level, 18 of the EU’s member states are known to have mandatory policies with two having voluntary status. Unfortunately, the study was not able to identify the status of the remaining eight member states. On the other hand, the vast majority of member states allow local governments to voluntarily apply green procurement policies.

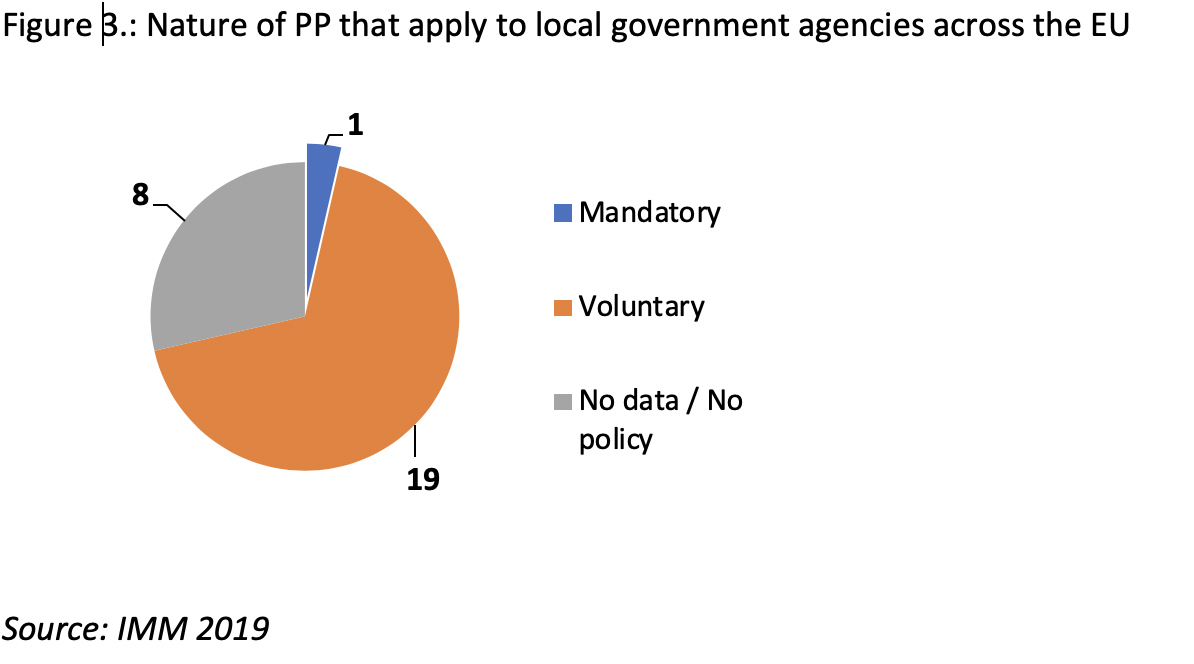

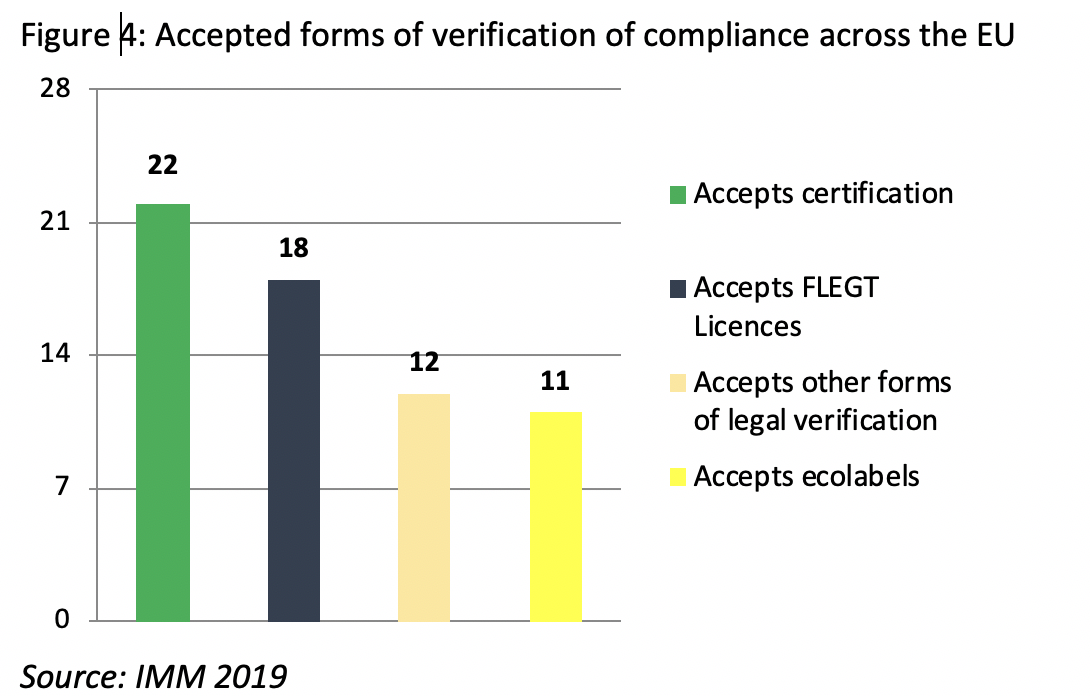

Figure 4 indicates that the policies of the member states contain a variety of means of verification of compliance. The most common, in fact universal, acceptable means of proof of legality and sustainability is through certification, usually FSC or PEFC.

The second most common acceptable form of verification is that of FLEGT Licences, mentioned by name within the policies of 18 countries. Twelve countries also allow for other forms of verification, ranging from third–party verification of legal compliance, through to forms of self-declaration. Ecolabels, in particular the EU Ecolabel and the Nordic Swan Ecolabel, also feature in the policies of 11 countries.

The “legal and sustainable” hierarchy and the status of FLEGT

In terms of their definitions of ‘legal’ and ‘sustainable’, the procurement policies can be divided into four broad groups.

- Those that have developed detailed sets of criteria for ‘legal’ and ‘sustainable’. The criteria derive from a variety of sources and inputs, including, generally, a multi-stakeholder consultation process, and they can be subject to revision in the light of developments. As reported by the Standing Forestry Committee5, in almost all cases certain social criteria are included and there is a focus on origin and production of wood and timber products, as opposed to life-cycle performance overall. All these countries have learned from one another’s experiences, and, sometimes, adapted their definitions accordingly.

- Those that take their definitions from the EU’s common GPP criteria, where compliance with the EUTR is a basic condition4.

- Those that use the terms ‘legal’ and ‘sustainable’ without setting out detailed definitions of exactly what these terms mean.

- The fourth group is just one country: Germany. It accepts only products certified by the two main global forest certification schemes, FSC and PEFC, or “equivalent”.

There are three different scenarios evident across the member states when it comes to acceptance of FLEGT-licensed timber:

- accepting FLEGT-licensed timber second to sustainably produced timber (for example: “if sustainable is not available”) or,

- accepting FLEGT-licensed timber on equal footing with sustainably produced timber, or,

- accepting FLEGT-licensed timber as legal timber

Policy makers in a number of EU member states have flagged up difficulties with acceptance of FLEGT licensing on equal footing to “sustainable”, partly as VPA-related legislation varies from country to country and the absolute levels of silvicultural performance almost certainly will not stand comparison from VPA partner country to country (i.e. forest practices that are legally allowed in one country may not always be considered as being sustainable in another). Another practical difficulty raised was the lack of a FLEGT chain-of-custody system.

Accepting FLEGT timber as being second to sustainably produced/certified timber, or even less, merely as legal timber, is almost certain to cause additional hurdles in the market. In practice, it means that FLEGT-licensed timber is unlikely to be specified in public projects. It also means that FLEGT-licensed timber is unlikely to benefit from leadership or supplier consolidation effects.

For the purpose of their timber procurement policies, the UK regards a FLEGT Licence as evidence of `sustainability’ on equal footing with FSC and PEFC certification, and Luxembourg treats a FLEGT Licence as equivalent to ‘legal and sustainable’. A number of other member states with policies aiming at sustainability, but without detailed definitions, including Austria, Finland and Lithuania, also list FLEGT Licences as acceptable means of verification of sustainability. Belgium, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden, however, treat FLEGT Licences as adequate proof of legality, but not of sustainability (or, in Sweden’s case, of general ‘acceptability’).

The UK does not provide an explanation of why it treats FLEGT Licences as evidence of sustainability7, but the report8 that formed the basis for Luxembourg’s policy included the following argument: ‘It is generally believed that FLEGT Licences are stand-alone tools and thus have to be differentiated from those means directly addressing sustainability at a forest management unit level, e.g. certification. It is important that the Member States provide incentives for joining the FLEGT process and this can be done through public procurement policies. It is therefore suggested that the Luxembourg Government also explicitly accept FLEGT-licensed timber as meeting the government requirements.’

Most countries have not yet formally stated what status they will grant FLEGT-licensed timber in their procurement policy hierarchy.

FLEGT licensing in public procurement practice

As indicated above, there is very little government reporting of compliance with their own purchasing policies or monitoring of volumes of certified, FLEGT-licensed or otherwise verified timber involved in public procurement.

One country that has recently tried to measure the impact of its timber procurement policy is Belgium. A 2017 study9 of 140,000 tender notifications issued between 2011 and 2016 revealed that specification of FSC and PEFC was evident with over 1,800 specific mentions within tender documents. The same study indicated that FSC was specified within contract notifications on 88 occasions and PEFC in a single contract. It also revealed that FLEGT-Licences were not specified at all. The study could not reveal the volumes of material involved or whether the policy had been complied with.

The findings of the study are in line with the results of a workshop on FLEGT-licensed timber in public procurement that took place during the IMM Trade Consultation in Antwerp10, Belgium, and attended by around 50 trade and government representatives from Belgium and the Netherlands. When asked whether trade representatives had offered FLEGT-licensed timber in bids for government contracts, hardly anyone confirmed that they had and those that did failed to win the contract. Participants also flagged up a perceived lack of awareness of the wider benefits of FLEGT VPAs among decision makers shaping public procurement policies and specifying timber for public projects, especially at local level, where the bulk of purchasing takes place.